Why are they called asymmetric matchers? I don’t know. But, that’s what the Jest documentation calls them, so that’s what I’m calling them. (The Vitest documentation doesn’t call them anything in particular.)

Here are two of my many hot takes around testing:

- Tests solely exist to give us confidence that we can make changes to our code base—large or small—without accidentally breaking things.

- Tests that are more annoying then they are helpful will lead to your and your team deleting them and/or just abandoning testing.

Winston Churchill said that “perfection is the enemy of progress.” And this is somewhat true for our tests. Our tests exists to give us confidence that we can change our code. If they become too rigid (or brittle), they tend to slow us down more than they speed us up.

Secondly, when a test fails, it would be nice if the failure was laser focused to what went wrong. A minor change might break a whole suite of tests. This could be dozens or even hundreds of tests. Good luck tracking down exactly what the culprit was.

Consider this Person from examples/characters/person.js for a moment:

import { v4 as id } from 'uuid';

export class Person {

constructor(firstName, lastName) {

this.id = 'person-' + id();

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

}

get fullName() {

return `${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}`;

}

}The uuid library generates a random id every time. Sure, there are way to get around this—name mocking and stuff, which we’ll talk about later. But generally speaking, we don’t really care about the id.

Let’s say we just cared if they’re cool and they they have a first and last name that are strings. (I know, we have TypeScript, but I’m trying to make a point here.)

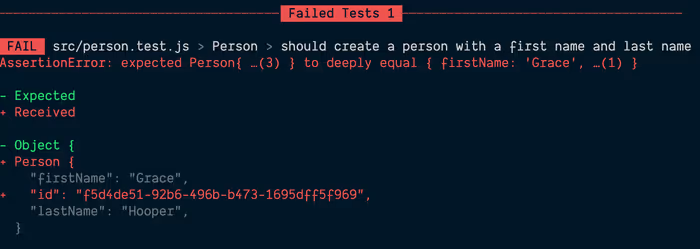

This well-meaning test is going to fail:

it('should create a person with a first name and last name', () => {

const person = new Person('Grace', 'Hopper');

expect(person).toEqual({ firstName: 'Grace', lastName: 'Hopper' });

});

We don’t really care what the id is but maybe we want to make sure that there is an id and that it’s a string.

it('should create a person with a first name and last name', () => {

const person = new Person('Grace', 'Hopper');

expect(person).toEqual({

id: expect.any(String),

firstName: 'Grace',

lastName: 'Hopper',

});

});We could even make sure that the string matches a certain pattern.

it('should create a person with a first name and last name', () => {

const person = new Person('Grace', 'Hopper');

expect(person).toEqual({

id: expect.stringMatching(/^person-/),

firstName: 'Grace',

lastName: 'Hopper',

});

});Put Another Way

Think of asymmetric matchers as that friend who’s cool with “close enough.” Unlike regular matchers (which expect an exact match), asymmetric matchers let you define the parts you care about and ignore the rest. They’re less strict, more forgiving—and sometimes, that’s exactly what you need.

Here’s the big thing: asymmetric matchers only care about one side of the comparison. They don’t compare the actual value to a specific expected result; instead, they’ll say, “Meh, I’ll just validate whether this meets my conditions, it doesn’t need to match the whole thing perfectly.”

Just Match What Matters with expect.objectContaining

You’ve got some giant object returning all kinds of extra data, but you only care about a few key properties? Perfect, objectContaining is your bud.

const strongestAvenger = {

name: 'Thor Odinson',

age: 1500,

weapon: 'Stormbreaker',

occupation: 'God of Thunder',

};

expect(strongestAvenger).toEqual(

expect.objectContaining({

name: 'Thor Odinson',

weapon: 'Stormbreaker',

}),

);Even though the original object has age and occupation, we only care about his name and his weapon of choice. Calling objectContaining lets us be specific about the parts that matter, and ignore the rest (because honestly, how many characters do we need on screen, right?).

Can you refactor the test for the person constructor to use expect.objectContaining just to make sure it’s got the correct first and last name?

Let’s Not Sweat Every Item: expect.arrayContaining

So right after you launch a new feature, your API doesn’t return exactly what you expected. Maybe there’s a new field randomly sliding into position two. Well, arrayContaining is like, “Hey, don’t worry about it, as long as your important stuff’s in there somewhere.”

const avengers = ['Iron Man', 'Captain America', 'Hulk', 'Black Widow'];

expect(avengers).toEqual(expect.arrayContaining(['Hulk', 'Captain America']));Notice that we’re not matching the exact sequence or every single Avenger in that list. We’re just making sure Cap and Hulk show up somewhere. It’s the “as long as they’re invited to the party” kind of test.

Searching for That Needle in a Hay Stack: expect.stringMatching

Ever had a string like an error message or some user input where you don’t know the exact wording, but you’re pretty sure it belongs? Welcome to stringMatching. Using regex (yes, the wizardry beloved by developers and feared by future maintainers), you can check if your log message or output string passes the vibe check.

const logMessage = 'User admin123 successfully logged in at 12:30 AM';

expect(logMessage).toEqual(expect.stringMatching(/admind+/));We don’t care if it’s admin123, admin456, or adminGoPats. As long as admin is followed by some digits, we’re good to go. Perfect for those unpredictable logs. Regular expressions to the rescue.

When to Use Asymmetric Matchers

So when should you use these? Here’s the pro tip: when exact matches don’t matter. You want to use asymmetric matchers when:

- You want flexibility with test data.

- You’re dealing with unpredictable fields that might change order, have extra values, or have variable content.

- You only care about a specific part of an otherwise noisy response.

Let’s be honest, as developers, we live in a world where APIs change, object structures pick up random fields, and arrays never seem to behave long-term. Keeping your tests passing without sacrificing thoroughness is key.

When Not to Use Them

Use asymmetric matchers sparingly, though. They can be a slippery slope. You don’t want to end up with every test being so flexible that they’re practically meaningless. Save these matchers for when being exact won’t provide much value and will just clutter your tests.

If you care about every property and value, go ahead and use toEqual or toBe like a normal matcher. But when the kitchen sink smells and you only care that the faucet’s working, asymmetric matchers are the way to go.

A More Practical Example

And that’s the magic of asymmetric matchers. Now, go forth and write tests that breathe! Keep ‘em specific to what matters, but not so specific that you get a test failure for wearing the wrong color hoodie.

This is all well and good with small, easy-to-grok examples, but let’s quickly glance at an example.