Let’s get a little philosophical. There are a lot of flavors of buttons in the world. For our purposes, we’re going to call these variants. One of the most common variants that we see out in the wild is the idea of having primary and secondary buttons. Additional examples include destructive buttons and disabled buttons, et cetera.

Using a Prop to Set the Variant

If we review a selection of existing design system implementations, we’ll see that far and away the most common way to allow consumers of your component library to set a variant is to provide a prop. What exactly you choose to call that prop and what values you’re willing to accept is up to you. As you’ll see, variant is a fairly popular choice, but appearance and kind are also used.

- Microsoft’s Fluent design system uses an

appearanceprop that is one of the following variants:primary,secondary,subtle,outline,transparent. - Atlassian’s design system also uses an

appearanceprop that can be eitherprimary,subtle,link,subtle-link,warning, ordanger. - IBM’s Carbon design system uses a

kindproperty that can be set toprimary,secondary,danger,ghost,tertiary,danger--primary,danger--ghost, ordanger--tertiary. - GitHub’s Primer design system uses a

variantprop that can be eitherdefault,primary,danger, orinvisible. - Twilio’s Paste design system uses a

variantprop as well with the following variants:primary,primary_icon,secondary,secondary_icon,destructive,destructive_icon,destructive_link,destructive_secondary,link,inverse_link, andinverse. - Shopify’s Polaris design system uses a

variantprop consisting ofplain,primary,secondary,tertiary, andmonochromePlain. - GitLab’s Pajamas design system also uses a

variantproperty that is one of the following:default,confirm,info,success,danger,dashed,link, orreset. - Adobe’s Spectrum design system also uses a

variantproperty that can be eitherprimary,secondary, ornegative. In their system,negativeis similar todestructiveordangerin some of the other systems. They also have two styles:fillandoutline, which are more likeprimaryandsecondaryin the other systems.

The end result is something that looks like this:

<Button variant="primary">Button</Button>

<Button kind="primary">Button</Button>

<Button appearance="primary">Button</Button>Using Boolean Props

Mozilla’s Acorn design system uses a primary prop as well as a disabled prop, each of which is a boolean. This approach will look something like this:

<Button primary>Button</Button>

<Button secondary>Button</Button>This syntax is really nice, but you risk ending up with someone passing in a conflicting set of variants.

<Button primary secondary>

Button

</Button>We can protect against this behavior with both type-safety and run-time checks, but it’s certainly more complicated. Given that the first approach is more popular, let’s look at implementing that first.

Implementing a Variant Prop

Let’s use variant as our prop since that seems to be a tried-and-true approach and possibly the most common based on my very cursory research above. For starters, we’ll have the following variants:

primarysecondarydestructive

We’ll start with our super-simple button component from the previous chapter.

import { ComponentProps } from 'react';

type ButtonProps = ComponentProps<'button'>;

export const Button = (props: ButtonProps) => {

return <button {...props} />;

};First, we’ll add our new prop and its accepted values to the ButtonProps type.

type ButtonProps = ComponentProps<'button'> & {

variant?: 'primary' | 'secondary' | 'destructive';

};Styling the Button

We’re going to start by using vanilla CSS and CSS modules right now. Later on, we’ll use Tailwind in a effort to make our lives easier and focus on the specifics of Storybook rather than CSS. But, you’re welcome to use whatever styling tools make you happiest. Storybook doesn’t have a horse in this race.

Let’s start by styling the button. We haven’t implemented any of these variants yet, so we’ll work on styling the primary button first and then go from there. In button.module.css, I have the following styles waiting for you.

.button {

align-items: center;

background-color: #4f46e5;

border-color: transparent;

border-radius: 0.25rem;

border-width: 1px;

box-shadow: 0 1px 2px 0 rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.05);

color: white;

cursor: pointer;

display: inline-flex;

font-weight: 600;

gap: 0.375rem;

padding: 0.375rem 0.75rem;

transition: background-color 0.2s;

}

/* Focus visible styles */

.button:focus-visible {

outline: 2px solid;

outline-offset: 2px;

}

/* Disabled styles */

.button:disabled {

opacity: 0.5;

cursor: not-allowed;

}

.button:hover {

background-color: #4338ca;

}

.button:active {

background-color: #3730a3;

}

/* Variant: secondary */

.secondary {

background-color: white;

color: #1f2937;

border-color: #94a3b8;

}

.secondary:hover {

background-color: #f1f5f9;

}

.secondary:active {

background-color: #e2e8f0;

}

/* Variant: destructive */

.destructive {

background-color: #dc2626;

color: white;

border-color: transparent;

}

.destructive:hover {

background-color: #b91c1c;

}

.destructive:active {

background-color: #991b1b;

}

/* Variant: ghost */

.ghost {

background-color: transparent;

color: #4f46e5;

border-color: transparent;

box-shadow: none;

}

.ghost:hover {

background-color: #f1f5f9;

}

.ghost:active {

background-color: #e2e8f0;

}We’ll add the style to our component and then bask in the fruits of our labor.

import styles from './button.module.css';

export const Button = (props: ButtonProps) => {

return <button className={styles.button} {...props} />;

};Our button now looks a little prettier.

So far, we’ve made the follow changes to our code.

diff --git a/src/components/button/button.tsx b/src/components/button/button.tsx

index 578f1d2..a6632c5 100644

--- a/src/components/button/button.tsx

+++ b/src/components/button/button.tsx

@@ -1,9 +1,11 @@

import { ComponentProps } from 'react';

+import styles from './button.module.css';

+

type ButtonProps = ComponentProps<'button'> & {

variant?: 'primary' | 'secondary' | 'destructive';

};

export const Button = (props: ButtonProps) => {

- return <button {…props} />;

+ return <button className={styles.button} {…props} />;

};Styling Our Variants

I already provided some classes for our variants, but we need to dynamically add them to our our component. One simple—but tedious—way to do this is to just append them to the className string. This might look something like this:

export const Button = ({ variant = 'primary', ...props }: ButtonProps) => {

let className = styles.button;

if (variant === 'secondary') className += ` ${styles.secondary}`;

if (variant === 'destructive') className += ` ${styles.destructive}`;

return <button className={className} {...props} />;

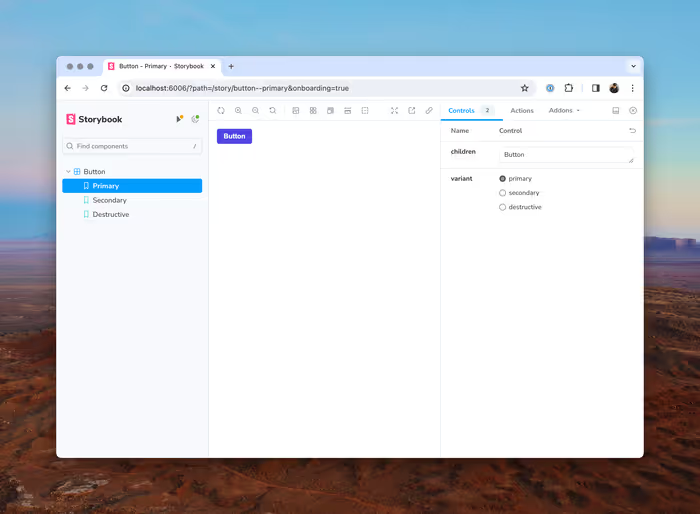

};Adding Stories for Our Variants

If we want to easily see each of these variants in Storybook, we’ll need to add additional stories for each variant.

export const Primary: Story = {

args: {

children: 'Button',

variant: 'primary',

},

};

export const Secondary: Story = {

args: {

children: 'Button',

variant: 'secondary',

},

};

export const Destructive: Story = {

args: {

children: 'Button',

variant: 'destructive',

},

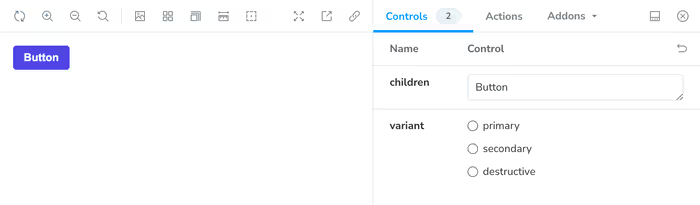

};We’ll now see each variant in our Storybook as well as an additional control for swapping between the variants.

Using clsx to Compose Class Names

clsx You made need to install clsx as a dependency using npm install clsx. If you’re following along with the example repository, then I’ve already included it in the package.json.

In our super simple example, appending to the string to compose the list of classes we want to apply to our button worked, but it’s going to get tedious as as the complexity of our button grows. We can use clsx, a handy utility for dynamically applying classes, to make our future lives a bit easier.

import { ComponentProps } from 'react';

import clsx from 'clsx';

import styles from './button.module.css';

type ButtonProps = ComponentProps<'button'> & {

variant?: 'primary' | 'secondary' | 'destructive';

};

export const Button = ({ variant = 'primary', ...props }: ButtonProps) => {

return (

<button

className={clsx(

styles.button,

variant === 'secondary' && styles.secondary,

variant === 'destructive' && styles.destructive,

)}

{...props}

/>

);

};clsx also supports an object-notation that you can use if you prefer.

export const Button = ({ variant = 'primary', ...props }: ButtonProps) => {

return (

<button

className={clsx(styles.button, {

[styles.secondary]: variant === 'secondary',

[styles.destructive]: variant === 'destructive',

})}

{...props}

/>

);

};clsx is somewhat helpful in this example, but it becomes a lot more useful when we have even slightly more complicated logic.

And with our initial variants in place, let’s play around with the controls a bit.